Domenichino’s The Last Communion of St. Jerome – a work about the superiority of communion under one kind

St. Jerome’s Last Communion, fragment, Domenichino, Pinacoteca Vaticana

St. Jerome’s Last Communion, Domenichino, Pinacoteca Vaticana, pic. Musei-Vaticani

St. Jerome’s Last Communion, fragment, Domenichino, Pinacoteca Vaticana

St. Jerome’s Last Communion, fragment, Domenichino, Pinacoteca Vaticana

When in 1614 this painting was hung at the main altar of the Church of San Girolamo della Carità at via Monserrato, it aroused such a great admiration, that the inhabitants of Rome went on veritable pilgrimages to visit it, praising its religious depth, power of expression, and realism. The work as well as its creator – Domenichino, were the talk of the entire artistic world. Only one man looked upon them with skepticism and jealousy. This was, the well-known in the city on the Tiber painter Lanfranco. A few years later he accused Domenichino of plagiarism, desiring to cover him in infamy.

When in 1614 this painting was hung at the main altar of the Church of San Girolamo della Carità at via Monserrato, it aroused such a great admiration, that the inhabitants of Rome went on veritable pilgrimages to visit it, praising its religious depth, power of expression, and realism. The work as well as its creator – Domenichino, were the talk of the entire artistic world. Only one man looked upon them with skepticism and jealousy. This was, the well-known in the city on the Tiber painter Lanfranco. A few years later he accused Domenichino of plagiarism, desiring to cover him in infamy.

This did not succeed. For centuries, the painting attracted crowds and was considered next to Raphael’s The Transfiguration and Daniele da Volterra’s fresco (Descent from the Cross), as the most outstanding painting work in Rome. Looking at it today it is difficult to understand why. Nevertheless, this fact teaches humility to everyone, not just an art historian – because it shows, how lively art is, and how fickle tastes and various artistic opinions can be.

However, let us start with the alleged plagiarism. The unknown to all Domenichino came to the Eternal City from Bologna in 1602 and became part of a group headed by master Annibale Carracci who was entrusted with the painting decorations of the main loggia in Palazzo Farnese. In time he started emerging out of the shadow of his teacher, painting religious works and portraits. However, when a new pope, Paul V, assumed the mantle, Domenichino began losing commissions, which ultimately led to him leaving the city. And it was then that Fraternity of St. Jerome from the aforementioned Church of San Girolamo della Carità through Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini (the cardinal legate in Bologna, and the patron of this fraternity) turned to him in 1612 with a proposal of completing a multi-format painting for the main altar of the modernized church. The aforementioned fraternity, which brought together laity devoted to charity and devotion, wanted to possess (as it would seem) a work similar to that, which hung in the altar of the Bolognese Church of San Girolamo della Certosa, and which was painted by Agostino Carracci, the elder brother of Annibale. Agostino had already been dead for ten years, but he did leave behind a work with a very rare iconographic motif, showing an unknown moment in the life of St. Jerome – namely his last communion. The painter "struggled" with the painting for over five years (1592-1597). Domenichino had to have known of it, even before he came to Rome. In accepting the commission he took advantage of a known composition, creating it anew, in a mirror reflection. He reduced the number of figures surrounding the saint, added a woman, and increased the number of angels at the base of the composition. There can be no doubt that he patterned his work on that of Carracci, but was it plagiarism? This is what Lanfranco claimed in 1620 when both painters competed to obtain the commission to complete frescoes in the Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle. Lanfranco even went so far as to disseminate prints with the Bolognese painting. Today, we would have said the work of Domenichino was a creative, but rather faithful interpretation of the original. This is how his biographer and greatest admirer – Giovanni Pietro Bellori also saw it, claiming that it was “a glorious imitation”.

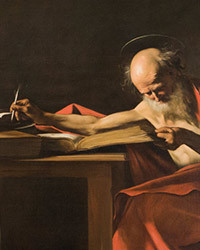

And thus in Domenichino's painting the rachitic, barely alive old man Jerome, adored by his students and having his hand kissed by Paula II (the granddaughter of St. Paula) takes communion from priests. The scene takes place in Bethlehem where Jerome spent the last thirty years of his life translating the Bible (Vulgate). There, he along with St. Paula established two monasteries – one for men and one for women. The students accompanying him (portraits of the representatives of the Fraternity of St. Jerome) and with care supporting his frail body, came from this monastery for men. On the other side, we can see Church dignitaries dressed in satin robes. Their liturgical dresses, corresponding to the Roman rite (subdeacon) and Greek (deacon) relate to two Church traditions, but also two regions where Jerome was active. The translator of the Bible died at an age of roughly ninety and was buried in a grotto under the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. The opening up of the composition onto a rather fancifully depicted Bethlehem landscape, which is filled with figures dressed in turbans (!), allows the artist to express his and his contemporaries' view of the inhabitants of the Holy Land. In order not to have any doubts that the painting does indeed show Jerome, the artists (similarly to Carracci in his Bolognese painting) painted a lion lying at his feet, since the Middle Ages an inherent attribute of the saint.

The painting had to move with its realism, with which the old body of the ascetic was presented, one in which life barely still burns. The toothless jaw, wayward gaze, dropped hands, and stiff legs remind us that every person’s life must come to an end. Jerome became a saint, not through martyrdom, but equally significant asceticism and the rejection of earthly goods. Why, however, was he shown in such an unusual scene? In order to respond to this question, we must recall the postulates that art and artists were supposed to fulfill after the Council of Trent, whose main task was to develop tools that would allow the Roman Catholic Church to effectively argue with Protestants and defend its own dogmas. Catholic artists were to, from now on, refer to the lives of saints and martyrs from ancient times in their works. They were to emphasize, as in the case of St. Jerome, the service to the Lord during their lives, but also asceticism, (mortification of the flesh, solitude, and celibacy). Martyrdom, as well as a pious lifestyle of those saints, were to be shown with a lot of emotion, but without unnecessary details or fanciful anecdotes. Paintings were to encourage prayer and devotion, but also provide the faithful with personal counselors and intercessors, to whom they may pray. Art was to fulfill a moralistic function, stimulate emotions, and strengthen the faith of each person, regardless of his education and social status, but also bind him with the Church through a knot of obedience and devotion. These, in turn, were to manifest themselves in acts of charity, penance, and devotion, but most of all participation in the Eucharist. Whether Jerome in his isolation really did take part in the Eucharist and take communion, we do not know, but that is how he was presented in the painting. This was a clear response to the criticism coming from Protestants, claiming that all that the faithful need is the salvific power of faith. The Protestants also brought back the right of the faithful to take the communion under both kinds (bread and wine), which had not been practiced in the Catholic Church since the Middle Ages, and in a sanctioned way since the Council of Constance (1415). At the Council of Trent, a lot of emphasis was placed upon this issue and it was the direct will of the Council to make common practice the giving of communion under one kind (bread). It was deemed, that it is sufficient for salvation and constitutes a true and full sacrament. The privilege of taking communion under both kinds was left to the priests celebrating mass. Individual cases of giving “communion of the chalice” were to be settled by the pope. Apart from that, fourteen situations were described, where communion under two kinds was permissible. One of these was the Viaticum (administered to those who are dying). And this is the kind of situation with which we are dealing in the painting.

It also cannot be overlooked, that in the work of Domenichino – ordered by the Fraternity of St. Jerome, wanting to modernize its church in the spirit of the Counterreformation – the central spot is occupied by the host, or more appropriately the religious ritual accompanying it, in which the barely alive Jerome participates.

At the end of the XVIII century, Domenichino’s canvas shared the fate of numerous works of art at that time – it was stolen by the French and taken to the Louvre. In the church itself, there is a copy by Vincenzo Camuccini from 1797. When after the fall of Napoleon, the painting was returned to Rome it found a new home in the Vatican Pinacoteca, where it can still be seen today, although it does not attract the crowds it previously had. The great esteem it enjoyed in the past can be testified to by the fact that its second copy, this time in a mosaic, was placed in one of the altars of the Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano.

St. Jerome’s Last Communion, Domenichino, 1614, oil on canvas, 419 x 256 cm, Pinacoteca Vaticana